Laksmiina Balasubramaniam, Photo by Markus Winkler on Unsplash

Early on in the pandemic, many countries committed to developing digital contact tracing (D-CT) tools in the hope that these digital solutions would be an effective tool to help contain the spread of COVID-19. Yet, countries were scrambling to determine what type of app was most appropriate. Some countries, such as France and India, pursued a centralized approach to D-CT where information collected by the app is stored on a central server by the government. France, for instance, pursued this approach because it would be more useful for public health planning. Meanwhile, other countries, such as Singapore, Australia, and Iceland, opted for decentralized solutions where any information collected by the app is stored on the individual user’s device in order to maintain a higher standard of privacy for users (that the centralized approach may not adequately attain). Not only did countries have to navigate the risks and benefits of decentralized and centralized approaches, they then had to completely develop the app – a major undertaking.

An Unlikely Partnership

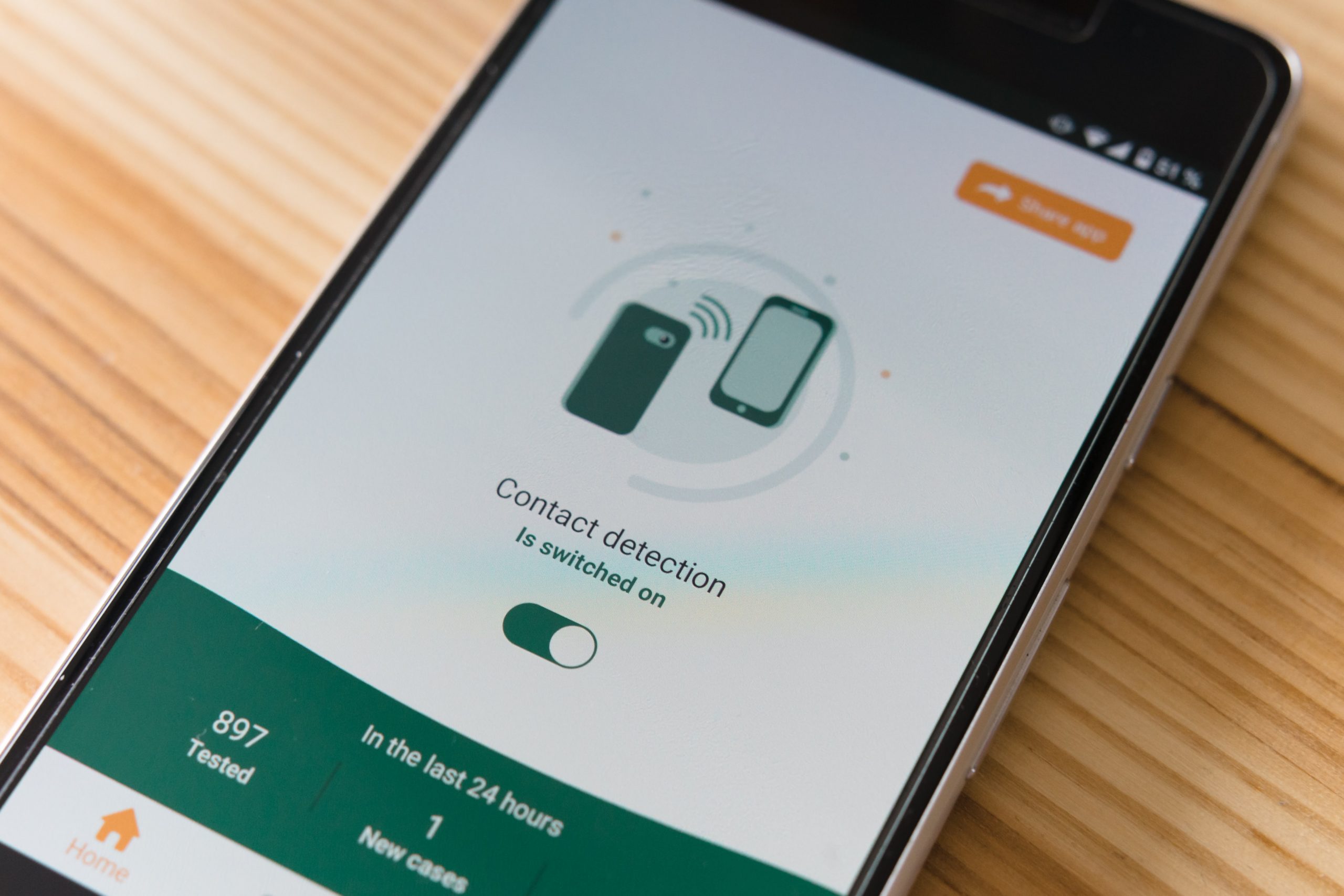

Then, in April 2020, Apple and Google announced that they were teaming up to enable the use of Bluetooth technology for D-CT to not only help governments and health agencies reduce the spread of COVID-19, but also protect user privacy. This collaboration resulted in the Google Apple Exposure Notification (GAEN) Application Programming Interface (API). The GAEN API provides the framework for governments to develop privacy-centric D-CT apps and enables decentralized D-CT apps to run in the background on a phone. This partnership and resulting API was a game changer: for good and bad.

(Photo/TechCrunch)

Love, Hate, or Love/Hate Relationship

The GAEN API was, and continues to be, supported by many privacy experts for its reliance on Bluetooth technology (rather than GPS) and decentralized information storage. The use of Bluetooth technology and storing information on users’ devices protects the privacy of users which could also facilitate higher levels of uptake. For these reasons, following the announcement of the GAEN API, some countries who were originally pursuing a centralized approach abandoned this for a GAEN API alternative, such as Germany. The GAEN API has since been adopted in many countries for their contact tracing apps including Canada, Switzerland, Ireland, and South Africa. Some countries such as Iceland have even indicated interest in switching from the app they had developed to one supported by GAEN API.

However, not all countries were happy about the Google-Apple partnership or the decentralized requirement. France was particularly vocal against the Google-Apple partnership, the GAEN API’s decentralized requirement, and the role Google-Apple had in the pandemic. This attitude arose for two reasons. First, since the GAEN API excluded centralized apps from being able to run in the background on a phone, centralized apps ran into functional issues – such as not working if another application was running – which means they would not be as effective at facilitating contact tracing and controlling the spread of COVID-19. Second, if the government chose to switch to a decentralized mode of data storage, the government would lose the benefits of a centralized system, namely the ability to collect information about aggregate population movement (flow of people in different areas), the ability to track “near misses” – both of which would be beneficial for managing the pandemic – and as France claimed, the ability to provide greater security against the collection, storage, or circulation of the list of persons who had tested positive for COVID-19. Ultimately, some countries felt strong-armed into picking the GAEN API even when they preferred a centralised system to support their pandemic response.

Then there are countries – like the United Kingdom – that had a seemingly love/hate relationship with the GAEN API. The original NHS app used a centralized model and faced several issues. In April, the Guardian reported that the app would not work if the phone screen was turned off (requiring the screen to always be active would take a huge toll on battery life) or if another app was being used at the same time. While the government continued to devote significant amounts of effort and time into developing the centralized app, it failed to register substantial amounts of nearby Android and Apple devices and was therefore not useful. In June, it was reported that the UK decided to pursue a decentralized D-CT app using the GAEN API. Yet, one report in August stated that the UK has “stepped almost entirely away” from digital contact tracing applications after the GAEN API failed to meet experts’ standards. Finally, after many months of back-and-forth, in September 2020, the UK launched a decentralized contact tracing app using the GAEN API.

(Photo/The Atlantic)

The Dominance of the GAEN API

As the experience of the United Kingdom, and France in particular, illustrates, rejecting the GAEN API to maintain a centralized approach comes with its own problems surrounding functionality and effectiveness. This leads us to a discussion about the dominance of the GAEN API and the role of private tech companies in a public health crisis.

Google indicated that decentralized data storage was required because neither Google or Apple wanted to provide functionality that would allow for surveillance that could be abused. This is a legitimate concern. With centralized data storage, there are concerns of lack of transparency and risk of mission creep (i.e. when a project gradually expands beyond its original scope). For instance, with a centralized approach, there may be a lack of clarity on the limits of the use of data collected by governments.

This emphasis on privacy is commendable. However, it is worth noting that the focus on privacy protection through a decentralized model comes with a trade-off on data that could have been useful for understanding the spread of COVID-19 through a centralized model. Furthermore, this situation highlights a concern of allowing private companies to direct the approach to a pandemic response.

For example, France had asked Google-Apple to ease privacy restrictions on collecting user data given the country’s strong record on preserving privacy. Yet, these two tech giants did not make an exception for France. The question arises: why is this the decision of a private company and not that of the government and/or the public? An article by POLITICO highlighted the concern of the increasing, dominating role of Big Tech in dictating how governments respond to a health crisis. As expressed by Cedric O, France’s Digital Minister, deciding how to address a public health crisis should be determined by the government who is accountable to their citizens not by policy choices of individual companies or “US digital giants.”

Finally, Google and Apple have promised not to monetize the COVID-19 exposure notification and their solution specifically minimized the personal data generated by users…this time. Can we rely on big tech companies to always make the choice to protect privacy and forgo profits for the public good? If we cannot, we should be more appreciative of governments who are willing to push back. While France’s request of Apple to lift technological restrictions were rejected, its willingness to push against Apple could have encouraged other nations to advocate for concerns they felt were not addressed by the GAEN API solution.

Final Thoughts

As private companies, Google and Apple did not owe anything to any government. In fact, we should appreciate the effort these companies made to help governments across the world in their response to COVID-19. At the same time, we should be cognisant of the fact that following the Google Apple announcement, some governments felt effectively coerced into adopting the GAEN API model. The advantages for privacy protection with a decentralized model may make it a better alternative to centralized models. But for countries who debated the benefits of centralized vs. decentralized models and chose the former to better reflect the needs of their nation, it is worrisome that the decision of Google-Apple could have effectively limited their ability to pursue what was in their view the best option for their nation and limit the effectiveness of their COVID-19 response. We need to consider who we believe should be deciding how to balance privacy needs against effective contact tracing systems and public health responses in general – tech companies or the government?